Class Is in Session with José Luis Vilson: #TeachSoHard

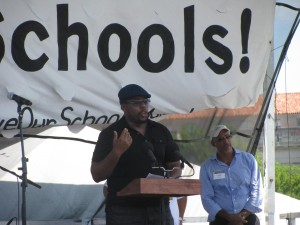

Just a couple days before the official school bell rang in the start of Mr. Vilson’s eleventh year of teaching, he was preparing his classroom for his new incoming students. Stacks of math textbooks filled some of his bookcases and the room was being rearranged, to make him accessible to his students within the confines of traditional schooling. Reflecting on his life and career, José Luis Vilson gives context to the educator, activist, and father he is constantly evolving into. He is the recent author of This Is Not a Test: A New Narrative on Race, Class, and Education, having made some major waves in the education field with his prolific analysis of the changes needed to better educate children, particularly those facing systemic barriers to success. Additionally, his website, past and present articles for places such as The Progressive, Edutopia, The Root, and recent spot on C-SPAN attest to his ability to expound on important issues. Vilson maintains his humility, hip-hop style, dry humor, sarcasm, and wit both on paper and in person.

José Luis Vilson is the son of parents from countries that have been historically at odds with each other. “My mother’s Dominican, my father’s Haitian and I am supposed to be a mix of that plus American because I wasn’t born in the Dominican Republic or Haiti.” He grew up knowing mostly about his Dominicanness, having been raised by primarily his mother. “I tried to ask about my Haitianness; that didn’t quite work out. I was never able to acclimate to Creole and then, I didn’t really see myself in there ‘cause again, my father was away so he made choices; I attached his culture with his choices. And that’s what it was. Whereas my mom, I mean, the Dominican piece was always there and I tried to integrate myself as hard as I could into that ideal but my physical features are often didn’t allow me to do that, especially in the confines of post-Trujillo-ism and how that hasn’t really left if at all, if you ask me. Even any sort of semblance to Africanism became an issue for too many of my relatives. Even if a lot of them have similar skin as me, the features were a dead giveaway that I had African in my blood. Like, yeah. No kidding.”

His early experiences with how his phenotype and skin tone affect his interactions with his family and peers were some of the challenges he had growing up in Lower East Side. “I could of danced the best merengue…I could have told you about such-and-such artist…anything, and it wouldn’t have worked. My Spanish, too, wasn’t all that great. My mom wanted for me to focus more on English than Spanish.” Vilson learned a lot of his reading and writing in Spanish from reading the Bible, teaching himself how to do it. “I don’t remember having too many male figures to look up to, if at all. My stepfather is a full-blood Dominican man who had serious issues with Haitianism and, of course, my Haitian father as well. He took out a lot of that on me, so that was a lot of fun as well (sarcasm). So, of course that’s another element of Dominicanism, right?” Vilson has a much better relationship now with his stepfather and described the early turbulence of having a lack of guidance as a young boy in public school, and how being in private school as he grew up brought its own set of challenges. “There’s another layer of religion and Catholicism and what you’re supposed to be doing versus what I see my friends doing. In high school it’s even worse because [it was a] predominantly white institution and you often get tokenized when you’re in the honors classes.” He navigated figuring himself out, carving out and walking his own path from a young age.

Vilson went on to study at Syracuse University. “I shaped my identity somewhere in [college] just because that was the one space where I was able to explore my identity in the context of everything else. I often say that I didn’t learn as much in my actual college courses as I did in my extracurriculars so being part of so many different organizations, getting a history lesson whenever I went, and listening to so many different speakers really shaped me. At some point, I was like, “You know what? I’m 100% this, I’m 100% that. I am all these things and that’s going to have to be what I’m dealing with. I’m not part this, I’m not part that. I’m just going to embrace it,” he said. He was the first to graduate from college in his immediate family, having gotten a higher education degree.

José decided to study Computer Science because of one of his hobbies growing up. “I had wanted to be a video game maker. I was really into video games growing up. I would spend 10 hours straight just playing games. Obviously there’s an element of escapism there. I just wanted to play games; I wanted to make them, I wanted to see what would come of it.” The same organizations that helped to shape his identity also laid the foundation for his career as an educator. “I think my first real involvement was La Lucha, which was Latino Undergraduates Creating History in America. My first year, I was exposed to so much culture, like what it meant to be Latino and to be radical Latino, which was pretty awesome. My second one was the Student African American Society, which was at that point the premier organization of color because they had a foundation of real radicalism and activism. They would have the Black Panthers, Bobby Seele hanging out in their house and the Young Lords hanging out at their house and these were real activists.” For Vilson, being a part of those organizations made him quickly realize that he could do a lot more with identity and culture than computer science. “By junior year, I was elected to be the education chair for La Lucha, which at that point was considered the president.” He had already wished to be given a shot to share his skills. “They gave me the chance and I did a whole lot more. I started doing things like workshops, bringing people in…” In developing his facilitation skills, Vilson saw himself teaching and went for it. “I could probably do a lot better if I give myself the opportunity to teach other kids a better way of doing things. And they can do it with someone that they can almost immediately trust. So that was my angle there.”

Vilson went on to do the New York City Teaching Fellows and did his masters degree at City College. “I was teaching at the same time that I was doing my masters so my day was 6am to, some days, 9pm. I had to come off [work] here, get to City College and I’d be in class until 9.” The process with Teaching Fellows was intense, but José didn’t take it for granted. He spent six months prior unemployed after graduating from his undergraduate career. From temp job agencies to alumni events to a basic data entry job, he was relieved to begin his career as an educator. “When I got accepted into NYC Teaching Fellows, I was like, “Oh my goodness. Okay so, I got it. We’re going to do this.” I took a vacation for like 3 days, Memorial Day weekend in Miami but that was already planned, like even before I had got this job but my last day of work was on a Friday. My first day of training was on a Monday…no days off. I decided, not taking anything for granted, Imma go in.”

Teaching these last 10 years has been a rollercoaster for José. “I think that maybe my first year was perhaps one of my best years only because I was just like ‘I gotta prove myself, I gotta do X, Y and Z and make sure I’m on top of my game.’ I got some help. I was grateful for some of my co-teachers around the building. But, it’s been up and down. My worst year was actually my fourth year, interestingly enough. There was this one class that came in. It tore me down. I was like, “How?!” There wasn’t anything that I felt I could possibly do besides survive. And even the teachers who had more experience than I did, they all just said, “We just do what we can…just to make it out.” That was the first time I had experienced that in this school.” He remembers feeling he couldn’t teach at the school, that it just wasn’t sustainable. “There were classes where I had good days and bad days. There are classes where [I felt] like, ‘they’re hard to teach but they can be taught.’ And then there was one class that I just felt like, “There are only seven or eight kids who actually want to learn and I’m going to teach them, and then the other 20 or so, I’ll get to you whenever you’re ready.” And that’s how it was. It was an ugly moment for me and people recognize that but… yeah, it was like that. It was tough. After that though, it’s been good.”

Vilson has also had the chance to become a math coach, which meant being an instructional coach, going to different classes, and being the liaison between administration and the teachers. “It was a good thing for me to experience because I got to see some of the highs and lows of like everything. I got to be the leader that I wanted to be, even as the youngest teacher in the building. Being this math teacher, I was still doing what I needed to do and I think I did a fairly good job of putting some things in place. Like, model lessons, work collaboratively, the way that we do our units…that was me. I was happy about that.”

I.S 52 is located in Washington Heights, which has given José a deep experience of teaching students with his Dominican heritage as well as other similar ethnic backgrounds. “This school was at one point 90% Dominican. That’s kind of come down a little bit thought because of the population. You have a lot of Central and South American kids coming through.” He has realized that being so entrenched in the Dominican community has caused teachers to develop stereotypes about the kids, citing the behaviors instilled in them. “Like, the kids that came directly from the Dominican Republic and came from certain sections, specifically from anywhere where there was even some sort of mandatory education, when they come into the states, they tend to be behaved fairly well. They have priorities; they’ll say, “God’s number one, parents number two, teachers number three,” and then everybody else, right?” Vilson also spoke about first generation Dominican students and how different they are, mostly about the privilege they don’t recognize they have amongst their own peers. He understands these stereotypes and looks past them to reach his individual and collective student body.

When it comes to the teaching profession itself, there are stereotypes of educators. Coupled with the machismo that is pervasive in society, Vilson’s career has gone against the grain of expectations. “I had always thought that teaching wasn’t a feminine profession but [that] it was feminized because what the powers that be needed out of teaching. They needed schools to run the way they do. I think as a man in this profession, I have a sense of needing to do things differently and giving people an alternative perspective of what manhood could be than what is often preferred out there, right? So I have been emotional in front of my kids when they graduate. I’ll be real emotional.” Because of the demands of teaching, he feels teachers need to have a full range of emotions for themselves because that’s a part of the self care, recognizing how much he has had to learn with emotional well-being.

“I do love teaching. There are things about teaching that I would never give up. But I also know this system does not allow for our kids to flourish as they should. And I’ve been evidenced to a lot of that stuff too.” The activist in Vilson has continued to be vocal in his teaching career. He has used his writing to address issues around race and class in education on many platforms, from his website to performing at a rally and recently, his own published book. “I started reading [my work], rereading, writing a lot of other good stuff and then I started thinking, “Okay maybe I need to write a book.” Because people are now saying, we need a book. Not to mention that if you look at education bookshelves, they don’t really have stories like mine. What I do mean by that is not in so much as my own experience, I mean, any sort of teacher books that weren’t…flowery. That’s what it was. A lot of it was really sugary and light, like, everything is going to work out in the end. No. That’s not how this works. So, I decided I was going to write that hard book and I started getting through this idea of the book publishing arena.”

After several query letters to agents and publishers shopping his work around, he understood how different his work was. “None of them said yes specifically but they were like, we like where you’re going, we think you have a lot of potential but we personally do not know how to market this, which I respected because I was like, okay well there aren’t many books like mine so okay, Imma handle that.” After five years, he was able to work with Haymarket Books to get his book out. It was challenging to complete. “The thing about that people don’t get is, there’s this whole big gap between when the book gets turned in and when the real book gets turned in, and for me that was like a good seven-month swing. So, throughout that process, my editor was like, “Let me look at your chapters; keep throwing me new chapters and see what you think.” She sent me some of these chapters with whole paragraphs just [crossed] out. She would move a whole bunch of different things or she’d change wording and she’d ask a lot of questions, and I wasn’t ready for that. I wasn’t ready! I’m not ready at all.”

Vilson admits to that time period being weird because of the things going on in his life. Around the same time his father passed away. “I was like, I don’t know what I’m going to do with this. I’m just going to drop this whole book thing because this is too much of a dream. And I wrote it out. I said, so, I don’t know what to do with this, and I waited at least another two weeks before turning in a chapter. And then I was like, no, this was meant to be, I’m going to make this happen. We did the whole funeral thing, it was good, and I was like, “My father was a big partier, like he wouldn’t have wanted this whole somber thing. It’s okay. Just roll with it.” And I just rolled and I started going in. And it made me a much better writer.”

4,000 plus copies later and no signs of slowing down, Vilson dedicates his passion to his journey in fatherhood. “[It’s the] best thing ever. I tell everybody. It’s so funny. People always say, oh, these are the steps you do in order to be a dad. And, I think I decided not to listen to a lot of people. There were a lot of rules I just did not follow. I mean, granted, I did give a gift like right after the pregnancy. I handled that, like okay, let’s be good. Swaddling, I took care of that. I handled that very well but of course my significant other decided to cheer whenever he got out of his swaddle and I was like, “You’re really gonna do this right now?” She tries to justify it and I’m like, “Nah son, chill. You know how hard it is to swaddle a baby like that?” And he’s a big boy too so like the swaddles? I feel like every other day I had to upgrade his blanket. My swaddles were on fleek though.”

He didn’t read much about embarking on becoming a father almost 4 years ago because he knew there was more to it than research. “It isn’t even about that; it’s about your relationship with your child and the things that you say, the non-negotiable. I’m fairly certain he knows we love him so that’s a good thing. I hug him up and kiss him up. All. The. Time. I’m sure it’s oppressive to him. I’m all up on him. Yeah. He’s the cutest little thing. I love him. Having a Dominican babysitter, you know, he gets his rice and beans. He gets his platanos, his puree, potatoes, [and] eggs. He doesn’t eat snacks but he eats that homegrown; this is why he looks like he’s 5 years old and not 3.” Vilson forged a new path with fatherhood different than his personal experience. With countless Black and Latino fathers breaking the stereotype that they are just largely absent, Vilson is in good company. “Black fathers tend to be the most involved and I think a lot of that has to do with the generational stereotypes that we were often accosted to. Thankfully for us, we decided, oh, we’re going to do this a little different. For me, I found my involvement to be non-negotiable. I probably spend too much time on other things, but if I don’t have all these other things to do, I can’t make ends meet for him so those are my negotiables, right? So I gotta be like, if I get this essay done, then I could put some money into a savings account. This commitment is something else.”

José Luis Vilson plans to continue writing about his experiences as an educator. He is working on EduColor and continuing to grow its capacity. His passion for teaching and addressing the disparities in education will continue to be prolific as he keeps adding to the conversation with his prolific writing. And what else? “Teaching. I [can] always do a better job.”

1 Comment